Big Pharma’s grip on Australia’s drug regulator

Pharmaceutical industry funding is shaping the TGA’s decisions—it’s a system primed to approve, not to protect.

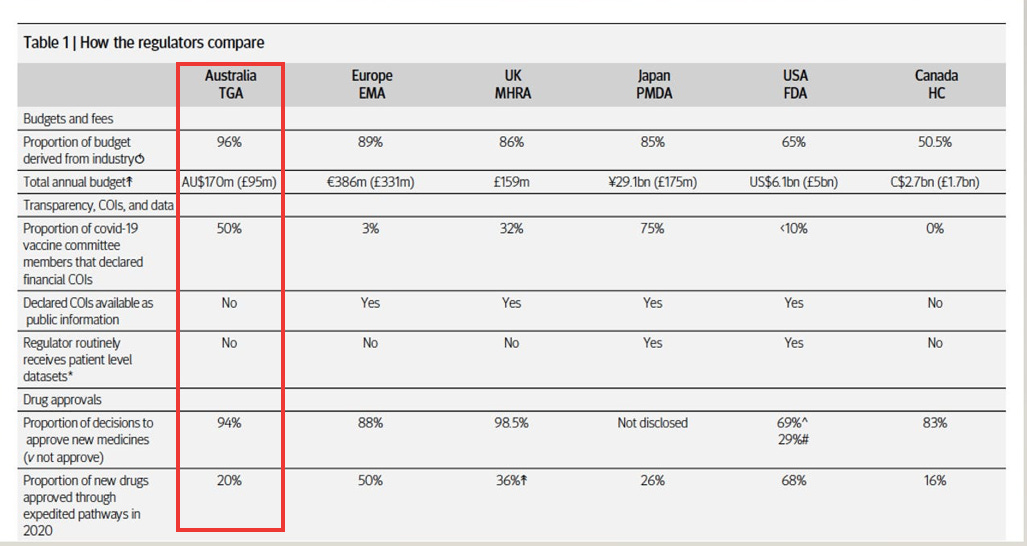

In 2022, I published an investigation in The BMJ exposing the lack of independence among drug regulators.

It revealed that 96% of the Therapeutic Goods Administration’s (TGA) operating budget comes from fees paid by the pharmaceutical industry.

To many, this represented an unmistakable conflict of interest.

How can Australia’s drug regulator claim to be truly independent when nearly all its funding comes from the very industry it is meant to oversee?

Yet some defenders of the system have pushed back.

They argue that there is nothing improper about the model—that it’s simply a form of “cost recovery,” similar to how doctors pay annual fees to maintain their registration with the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA).

If doctors’ fees don’t influence decisions at AHPRA, they ask, why would pharmaceutical fees influence the TGA?

On the surface, it sounds like a fair argument. But it falls apart under scrutiny.

It is not just about who pays—it’s about how they pay, what they receive in return, the scale of commercial stakes, and how much influence is granted in the regulatory process.

The two models are not comparable. And here’s why.

Concentrated power vs. diffuse funding

The pharmaceutical industry’s financial relationship with the TGA is concentrated in the hands of a few powerful players.

A small number of multinational companies—Pfizer, Merck, AstraZeneca, among others—provide a large share of the TGA’s total funding.

These companies pay millions annually in application fees and product registrations, making them critical to the agency’s budget.

If several of these companies were to pull back their submissions or challenge the cost structures, it would have an immediate and serious impact on the TGA’s finances.

This creates a silent but powerful dependency: the TGA has strong incentives, even if unconscious, to maintain a favourable relationship with its most important financial contributors.

By contrast, AHPRA’s revenue is spread across more than 850,000 individual health practitioners across 16 different professions.

No single doctor—or even a large group—can meaningfully threaten its financial stability. If one doctor stops paying their registration fee (ranging from $200 to $1200), AHPRA does not notice.

It is protected by the sheer size and diversity of its revenue base.

This distinction matters.

At the TGA, a handful of companies hold serious leverage. At AHPRA, no individual practitioner—or even profession—holds sway.

Transactional payments vs. standardised fees

The TGA’s funding model is highly transactional.

Pharmaceutical companies pay specific fees for services: evaluation of drug applications, listing of products on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG), priority reviews, and expedited pathways.

These are not simply administrative charges—they are commercial investments.

It’s money exchanged for regulatory decisions that unlock market access and future profits.

An approved drug doesn’t just recover the cost of the initial application fee—it secures years of additional income for the sponsor, and ongoing annual charges for the TGA.

And the numbers tell a story -- 94% of new drug applications submitted to the TGA are approved—suggesting the system is heavily weighted towards approving, rather than rejecting, applications.

By contrast, AHPRA’s registration fee is standard, annual, and completely disconnected from specific outcomes.

Doctors pay the same fee regardless of whether they are granted a specialty registration, investigated for a complaint, or disciplined.

There is no "payment-for-outcome” dynamic.

At the TGA, money is tethered to significant commercial outcomes. At AHPRA, money is tied only to the maintenance of professional registration.

Corporate billions vs. individual careers

The stakes for pharmaceutical companies are colossal.

Approval of a single blockbuster drug can generate billions of dollars in global sales.

Australia’s healthcare market alone—valued at over $200 billion annually—offers rich rewards for companies that secure swift entry through TGA approval.

Given the size of the prize, companies are highly motivated to leverage every tool available—payments, consultations, lobbying—to ensure favourable treatment.

By contrast, while a doctor’s career and livelihood are vitally important to them personally, the stakes are personal.

Most doctors are not multibillion-dollar enterprises.

They cannot hire lobbyists or exert strategic pressure on AHPRA.

The corporate financial muscle behind pharmaceutical companies—and the TGA’s dependence on it—creates a level of commercial risk that simply does not exist with AHPRA.

Access to policymaking

Pharmaceutical companies have formal, institutionalised access to TGA decision-making.

Through mechanisms like the Cost Recovery Implementation Statement (CRIS) consultations, industry groups routinely advise on regulatory reforms, fee structures, and approval processes.

Over time, many of the TGA’s most significant reforms—such as reliance on overseas approvals and the proliferation of expedited pathways—have been closely aligned with industry preferences.

This is not a conspiracy; it is a feature of a system where those who pay the piper call the tune.

Doctors, by contrast, have no such formal role at AHPRA and cannot buy access to policymaking panels.

Moreover, doctors cannot pay for priority registration or faster disciplinary reviews.

Investigations and licensing standards are upheld irrespective of fees paid.

Essentially, the pharmaceutical industry has a seat at the TGA’s table. Whereas doctors paying AHPRA fees, do not.

Safety vs. expediency

The public health stakes of drug regulation are enormous.

An incompetent or impaired doctor may cause serious harm to individual patients.

But if the TGA fails—if a dangerous or poorly tested drug is approved—the consequences can be wide-reaching.

Entire populations can be exposed to harm.

Hence, the TGA demands an even higher standard of independence and impartiality than medical licensing.

Yet its funding model places it in a structurally weaker position to maintain that independence.

The models don’t compare

The pharmaceutical industry’s financial relationship with the TGA is concentrated, transactional, high-stakes, and consultative.

Every structural feature increases the risk of bias, whether conscious or unconscious.

AHPRA’s relationship with its registrants, by contrast, is diffuse, standardised, low-stakes, and largely insulated from undue influence.

Superficially, both models involve fees paid by regulated entities. But in practice, they could not be more different.

If Australia is serious about protecting public health, it must recognise that 96% industry funding of the TGA is not merely "cost recovery."

It is a fundamental vulnerability—one that urgently demands reform.

Until the TGA diversifies its funding, strengthens its independence, and rebuilds public trust, the pharmaceutical industry's financial grip will continue to compromise Australia's drug regulatory system.

Because when a regulator’s loyalty tilts toward those who fund it—not those it serves—public health is no longer protected. It is sold.

I'm currently enjoying the benefits of two products that are on TGA's banned list, not because they are unsafe or ineffective. They're actually extraordinarily safe and effective to the extent that they threaten the profit streams of many multiple pharma products. The TGA is obviously fulfilling its primary, though not stated, function of protecting the financial interests of the piper whose tune they persistently play.

And we all know what they did to Pan Pharmaceuticals in 2003 - bankrupted by being forced to withdraw all its products primarily on the basis of a spurious claim that "someone" had suffered an adverse effect from just one of its products. A total witch hunt if ever there was one. The company's founder, Jim Selim, was awarded damages when it was found the TGA acted excessively, but his company had been destroyed.

All aided and abetted by the old bogey - mainstream media, piping away in chorus.

Re: “How can Australia’s drug regulator claim to be truly independent when nearly all its funding comes from the very industry it is meant to oversee?”

And to think that products approved by the industry-funded TGA can go on to be MANDATED for use…i.e. vaccines…

With TGA-approved and ATAGI-recommended COVID-19 vaccine products being GOVERNMENT MANDATED under threat of people losing their livelihood and participation in society for refusal to comply.

This travesty happened in a supposed ‘free country’…

And speaking of conflicts of interest Maryanne, are you looking into ATAGI?

See for example: ATAGI - Disclosures / Conflicts of Interest and historical information - this matter is STILL outstanding, 5 March 2025: https://vaccinationispolitical.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/atagi-disclosures-_-conflicts-of-interest-and-historical-information-this-matter-is-still-outstanding-1.pdf