Can’t we just let doctors be doctors?

FDA commissioner Marty Makary tried to explain that decisions belong to doctors and patients—not government panels. But CBS’s Margaret Brennan wasn’t ready to hear it.

It was one of the more cringeworthy TV interviews I’ve seen in some time.

Not because the guest said anything shocking, but because the host seemed incapable of grasping a foundational concept of medicine - doctors are meant to treat patients, not guidelines.

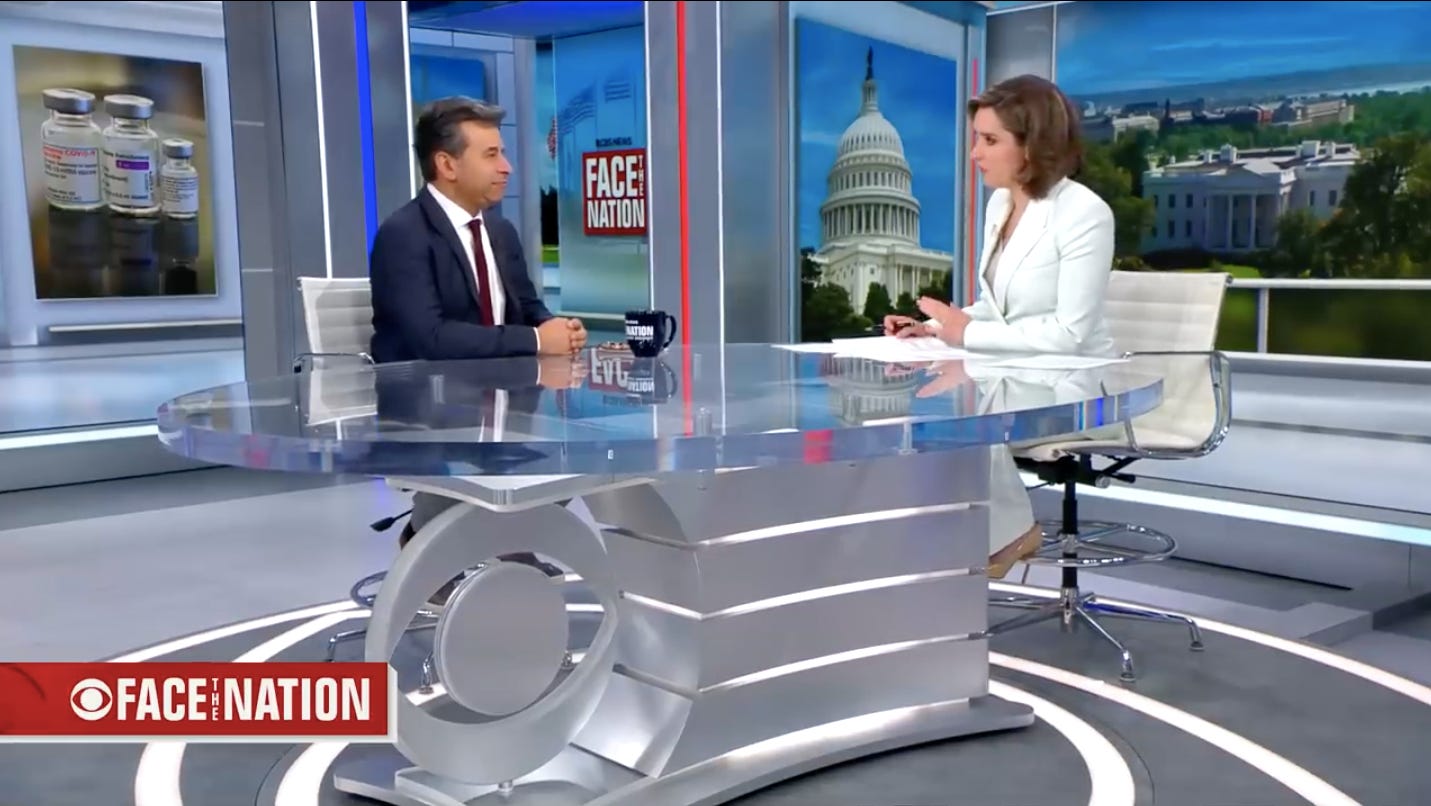

When FDA commissioner Dr Marty Makary recently appeared on CBS’s Face the Nation to discuss recent shifts in Covid-19 vaccine policy, he calmly and repeatedly made the case for clinical autonomy.

Decisions about whether to vaccinate healthy children or pregnant women, he said, should rest with “a patient and their doctor.”

But host Margaret Brennan wasn’t having it.

Like much of legacy media, Brennan seemed to expect a single directive from government—a rule to follow, a top-down mandate to repeat.

The idea that different patients might warrant different decisions, or that doctors should assess individual risks and preferences, was met with disbelief.