Is the FDA salvageable?

The FDA has been rubber-stamping drugs that barely work while Big Pharma cashes in. Now, with Marty Makary at the helm, can he fix a broken system?

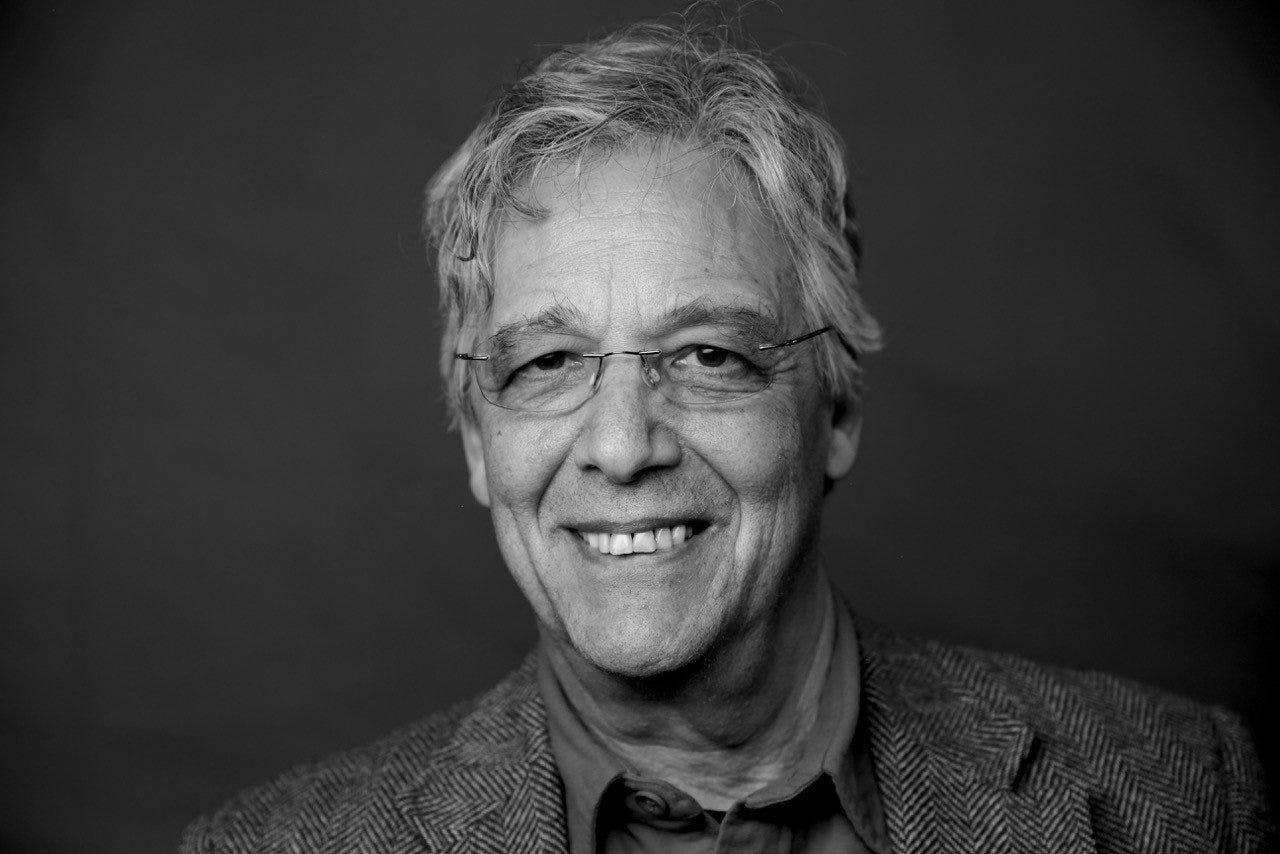

Dr Marty Makary—now confirmed as FDA Commissioner—inherits an agency that routinely approves drugs with questionable benefits.

At Makary’s confirmation hearing on March 6th, senators repeatedly hailed the FDA as the "gold standard" of drug regulation—a phrase meant to reassure the public that approved drugs are significantly effective.

But this claim is an illusion.

In 2013, Jonathan J. Darrow, a Harvard legal scholar and expert in drug regulation, published a scathing analysis in the Washington and Lee Law Review, exposing the reality behind this phrase.

Darrow’s paper, Pharmaceutical Efficacy: The Illusory Legal Standard, meticulously details how the FDA’s approval process does not require drugs to be meaningfully effective—only that they show some effect, no matter how trivial.

Since then, the problem has only worsened.

Makary has spent years criticising medical waste and corporate influence in healthcare. But now, as the new FDA Commissioner, can he reform an institution this compromised?

The "gold standard" that fails the public

The phrase "gold standard" suggests uncompromising scientific scrutiny. However, under U.S. law, there is no specific level of efficacy required for a new drug to be approved.

The FDA’s legal framework, Title 21 of the U.S. Code, demands only "substantial evidence" of benefit, but there is no requirement for demonstrating any particular magnitude of benefit.

Darrow explains: "The standard is almost entirely illusory because it leaves to the drug sponsor the ability to specify any non-zero level of efficacy.”

This ambiguity explains why many widely prescribed drugs offer only marginal benefits.

Consider antidepressants like Prozac and Zoloft. Research indicates that the majority of patient improvement could be due to the placebo effect, not the drug itself.

Yet, because these medications show statistical improvement in clinical trials, they meet the FDA’s approval threshold and are marketed as transformative treatments.

Darrow reported in 2021 that most newly approved drugs (69%-98%) fail to provide substantial benefits over existing therapies.

Cherry-picking evidence

Another critical flaw in determining drug efficacy is selective trial reporting. Drug companies conduct numerous clinical trials, but the FDA only requires two successful trials for approval—regardless of how many have failed.

This means a company could run 10 trials, discard eight that show no benefit, and submit the two positive ones. This practice is precisely how some SSRI antidepressants were approved.

In a major exposé, researcher Irving Kirsch and his colleagues used the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) to obtain unpublished clinical trial data on six widely prescribed antidepressants.

FDA approval had been granted based on twelve trials (two per drug). Yet, a FOIA request uncovered 47 trials—many of which showed no meaningful difference between the drug and a placebo.

The registration of trials on public registries like ClinicalTrials.gov was intended to improve transparency, but enforcement remains weak. Many trials that should have been disclosed are not, and financial penalties for non-compliance are rarely enforced.

The result? A regulatory loophole that allows ineffective drugs to be marketed as evidence-based solutions.

Misleading people with statistical tricks

Beyond cherry-picking trials, statistics can be manipulated to make drugs seem more effective than they are. One common tactic is presenting relative risk reduction instead of absolute risk reduction.

Take statins, the cholesterol-lowering drugs prescribed to millions. Clinical trials often claim statins reduce heart attack risk by 30%. However, this figure refers to relative risk—not absolute risk.

In reality, the absolute risk reduction is often less than 2%. This means that out of 100 people taking statins, 98 see no benefit at all. Yet, because the effect meets "statistical significance," statins are approved and aggressively marketed as essential for heart disease prevention.

Another example is the diabetes drug saxagliptin (Onglyza), approved by the FDA in 2009. Marketed as a breakthrough for blood sugar control, later studies showed the absolute reduction of HbA1c—a key measure of blood sugar—was negligible (0.4% to 0.9%).

Worse, in 2013, a large-scale trial revealed a possible increased risk of heart failure. Yet, the drug remains on the market, illustrating how weak efficacy standards allow ineffective (or even harmful) drugs to persist.

The cost of an ineffective system

Weak efficacy standards don’t just mislead patients—they can also lead to financial strain. This issue is particularly egregious in oncology.

New cancer drugs routinely cost over $100,000 per year, yet many extend life by only weeks or months, if any. Families may drain their savings, hoping for a meaningful survival benefit, only to later learn that the drug offered little more than a statistical blip.

In 2016, the FDA granted accelerated approval to olaratumab, which was hailed as a breakthrough for soft tissue sarcoma. However, it was withdrawn in 2019 after further research failed to show any survival benefit.

The FDA had granted approval based on early-stage trials that created the illusion of efficacy.

This isn’t just a regulatory failure—it’s a moral one.

Why we need clearer drug labelling

Darrow argues that drug labelling is a major part of the problem. "There’s no requirement for pharmaceutical companies to offer any scale of benefit, in a manner that patients can understand," he wrote.

"Knowing how well a drug might perform relative to an alternative—through clearly presented data—allows doctors and patients to decide whether it’s worth [it]."

He draws a parallel with sunscreen labelling. "A consumer easily understands that SPF30 will give greater protection than SPF10. So why don’t we have better drug labelling?"

Alternatively, he has suggested that drug labels could adopt a similar approach to food labels, “with data presented in columns that show key information and allow for side-by-side comparison.”

Or, the labelling for sleeping pills could “indicate the number of minutes it took those who had used them in clinical trials to fall asleep compared with a placebo.”

The lack of transparency only benefits the pharmaceutical industry from increased drug sales.

Can Makary fix the FDA?

Marty Makary has been a relentless critic of medical waste, unnecessary treatments, and corporate influence in healthcare. However, reforming an agency so deeply entrenched in industry influence is an extraordinary challenge.

Drug companies pay billions in user fees to the FDA, and in return, they influence regulatory decisions. Laws governing drug approval have remained largely unchanged for decades, ensuring that the FDA prioritises speed over scientific rigour and drug safety.

The FDA continues to approve drugs with minimal benefit, it allows companies to cherry-pick positive trials while ignoring negative ones and misleads doctors into believing that weak drugs are more effective than they are.

The public assumes that FDA approval means a drug is significantly effective.

It does not.

If Makary is serious about reform, he must push Congress for sweeping legislative changes to dismantle the pharmaceutical industry’s stranglehold on drug regulation.

The FDA was created to protect the public—not to serve as a rubber stamp for Big Pharma. Right now, the FDA is failing in its mission.

The question is no longer whether the FDA is the "gold standard" of drug regulation. It’s whether the agency is salvageable at all.

Further reading:

Interesting how language works. The "gold standard" originally applied to money and fell out of favor long ago. Now we have fiat currency that is a lot like the placebo effect.

The Relative Risk Reduction (aka VE) trick was used to good effect during COVID. Everyone touted 95%, and of course no one quoted the Absolute Risk Reduction, which from memory was .84%. (And even that figure looks entirely bogus now, and is quite likely to be negative).