Is the war on saturated fat finally going to end?

They called us fringe. Dangerous. Irresponsible. But we were right about saturated fat. Is the medical establishment finally ready to admit it?

For decades, defending saturated fat was considered scientific heresy. Suggesting that butter might be better than margarine—or that full-fat cheese wouldn’t clog your arteries—was enough to get you labelled as fringe, irresponsible, even dangerous.

I should know. I was there.

Catalyst controversy

In 2013, I produced a two-part investigative series for ABC’s television program Catalyst, examining the demonisation of saturated fat (part 1) and the widespread use of cholesterol-lowering drugs known as statins (part 2).

The first episode traced the origins of the diet-heart hypothesis and the work of Ancel Keys, whose Seven Countries Study laid the foundation for decades of dietary advice warning against saturated fat.

The medical dogma was firmly entrenched: saturated fat raised cholesterol, and cholesterol caused heart disease.

But the science behind it was shaky—built on cherry-picked data and upheld more by consensus than by critical evaluation.

The series featured experts like Dr Michael Eades, an early advocate for low-carb, high-fat diets; cardiologist Dr Stephen Sinatra; nutritionist Dr Jonny Bowden; science journalist Gary Taubes; and cardiologist Dr Ernest Curtis.

Behind the scenes, I worked closely with pioneers such as Dr Uffe Ravnskov (The Cholesterol Myths) and Dr Malcolm Kendrick (The Great Cholesterol Con), both of whom had been challenging the orthodoxy long before it was safe to do so.

In the program, Eades, for instance, highlighted the absurdity of the prevailing narrative: “You very seldom see the words ‘saturated fat’ in the public press when they’re not associated with artery clogging. So it’s like it’s all one term – ‘artery clogging saturated fats.’”

Bowden, who co-authored The Great Cholesterol Myth with Sinatra, was just as direct, calling it “a huge misconception that saturated fat and cholesterol are the demons in the diet,” adding, “It is 100% wrong.”

Sinatra traced the origins of the myth, arguing that “saturated fat has been vilified for years because of the cholesterol theory.”

And Taubes, author of Good Calories Bad Calories, known for his meticulous dismantling of diet dogma, cut to the core: “There’s no compelling evidence that saturated fat is involved in heart disease.”

The program also gave voice to the prevailing view, including contributions from Dr Robert Grenfell, Director of the National Heart Foundation, and cardiologist Professor David Sullivan, both of whom vigorously defended the status quo.

Nonetheless, the backlash was immediate, vicious, and unrelenting.

The media turned on me. There were calls for my sacking. The experts who challenged the cholesterol dogma were denounced as “fringe.” And ultimately, the ABC pulled both episodes from its website—despite its own internal review finding no factual inaccuracies.

Much of the outrage came from the medical establishment’s unwavering certainty. Sullivan, who appeared in the program, doubled down in The Conversation:

“It’s not even debatable – saturated fat is bad for you,” he proclaimed. That was the orthodoxy. That was what I was up against.

The other voices

Of course, I wasn’t alone in beating this drum—I couldn’t possibly name everyone who helped keep the evidence alive.

The late John Yudkin had warned as early as the 1970s that sugar—not fat—was the real culprit in heart disease, only to be mocked and marginalised by his fierce opponent, Ancel Keys

Ravnskov and Kendrick were among the first to publicly challenge the cholesterol hypothesis in popular books.

And in 2013, The BMJ published a commentary by cardiologist Dr Aseem Malhotra titled “Saturated fat is not the major issue,” attacking decades of flawed advice and warning that the obsession with lowering cholesterol may have worsened heart disease.

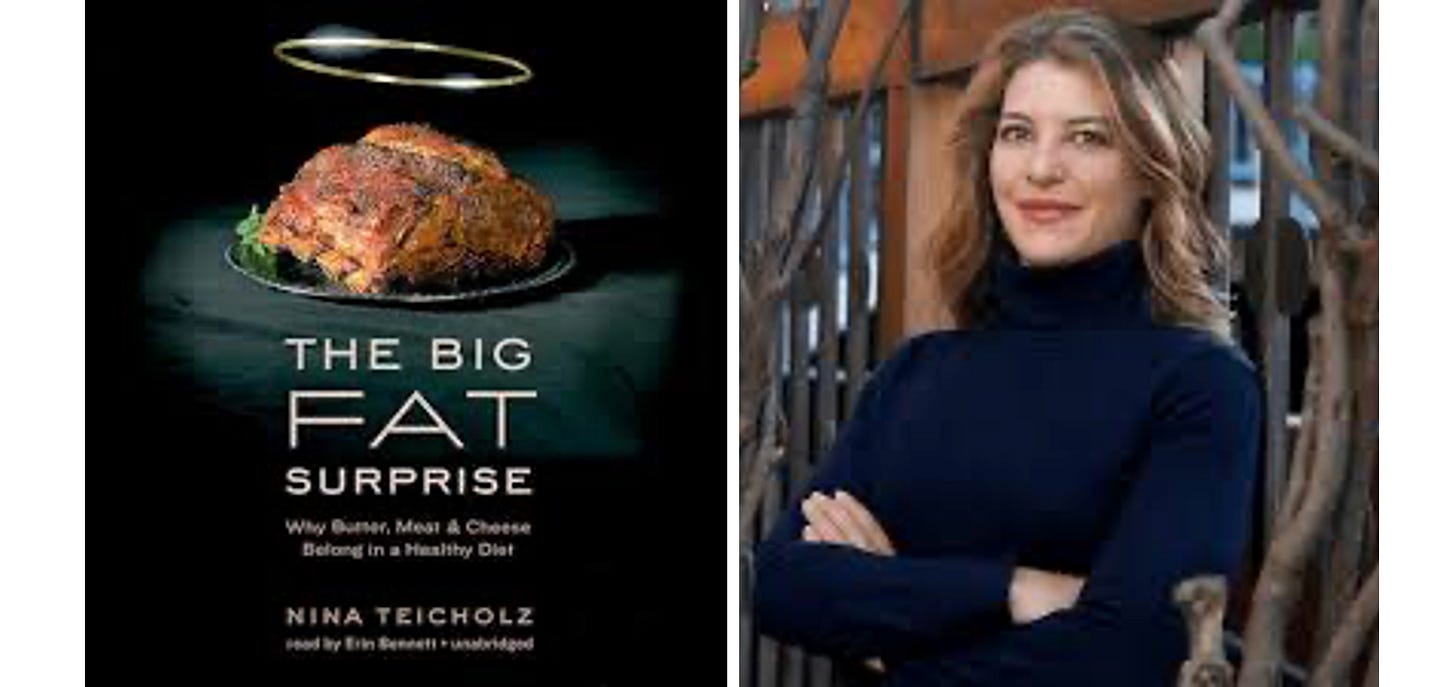

Then came Nina Teicholz’s The Big Fat Surprise in 2014—a deeply researched, bestselling exposé that brought the issue to the public’s attention.

Teicholz documented how weak science, political pressure, and food industry lobbying created a false consensus that demonised fat and distorted public health policy.

Researchers like Christopher Ramsden and colleagues added more data. In 2016, they assessed the diet-heart hypothesis by re-analysing the long-buried Minnesota Coronary Experiment and published their findings in The BMJ.

They showed that replacing saturated fat with linoleic acid (from vegetable oils) did indeed lower cholesterol—but paradoxically increased mortality, particularly from heart disease.

More damning was the fact that these data had been buried for decades—suppressed at a time when they might have reshaped dietary policy.

Researcher Dr Zoe Harcombe played a vital role in deconstructing the evidence base behind dietary guidelines, exposing the weak foundation for saturated fat restrictions.

In South Africa, Professor Tim Noakes—once a champion of high-carb diets—reversed his stance after reviewing the science and became an outspoken advocate for low-carb, high-fat nutrition.

His shift led to a high-profile trial, which he ultimately won.

I’ve continued to write in this space, including a 2020 BMJ article reporting on U.S. experts calling for the removal of the saturated fat cap from dietary guidelines—which is currently set at 10% of daily energy intake.

In Australia, the National Health and Medical Research Council is currently reviewing the nation’s own dietary guidelines, scheduled for delivery in 2026.

The review, led by Professor Steve Wesselingh, has promised to “ensure they reflect the best and most recent scientific evidence.” Let’s see.

Now, Makary’s promise

For the first time, real change may be coming—not from the margins, but from the very top of the U.S. health establishment.

Last week, in a press conference, FDA Commissioner Dr Marty Makary addressed his skepticism of the U.S. dietary guidelines.

“Since Ancel Keys in the 1960s decided to demonise saturated fat with a hypothesis that was supported with data that was incomplete and methodologically flawed in his Seven Countries Study,” Makary said, “the medical establishment locked arms and walked off a cliff together.”

It was a stunning moment—not because the criticism was new, but because it was coming from someone in an official position to do something.

For the head of the FDA to so directly reject the foundation of half a century of nutrition policy signals a seismic shift. “We’re going to ensure that the new guidelines are based on science and not medical dogma,” Makary promised.

Back in 2022, while writing his book Blind Spots, Makary reached out to me. “I just love your work,” he wrote in a message. “Reading your work on Ancel Keys now.” He told me he had cited my reporting in his manuscript.

At the time, I was grateful for his support, but I never imagined he’d become FDA Commissioner—let alone publicly challenge the very dietary guidance I’d been professionally punished for questioning.

Now, what was once ridiculed as fringe is being echoed from the highest levels of public health.

A turning point?

It’s taken decades. The cholesterol hypothesis wasn’t just a scientific claim—it became a professional litmus test. To challenge it was to risk your funding, your career, your credibility.

Many of us paid that price.

Even now, entrenched interests remain.

The U.S. dietary guidelines committee—particularly the saturated fat subcommittee—has been heavily criticised for its conflicts of interest. Many members have ties to plant-based advocacy groups or have built careers promoting low-fat diets. Independent voices remain marginalised.

But the tide may be turning.

U.S. Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has also raised concerns about industry influence over dietary guidelines and hinted that upcoming revisions may elevate full-fat dairy and remove the saturated fat cap altogether.

If those changes come to pass, it would mark an historic course correction—one rooted in evidence rather than ideology.

Will the medical establishment apologise? Will the legacy media acknowledge its role in enforcing the old narrative? Will those of us who were silenced be offered any kind of reparation?

Probably not.

But that’s not the point. The point is that we may finally be seeing the collapse of one of the most destructive public health myths in modern history.

And if Makary and Kennedy stay true to their word, the next generation of dietary guidelines may reflect the science—and not the politics.

For those of us who’ve waited decades, it’s not vindication we want (although that would be nice)—it’s change.