Time to ban drug advertising on TV in America?

Direct-To-Consumer Advertising (DTCA) of prescription drugs is back in the headlines after Robert F. Kennedy Jr made an election promise to ban it.

Democratic presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy Jr recently said that if he becomes president, he will ban pharmaceutical advertising on US television.

“It’s not good to have pharmaceutical advertising on TV,” said Kennedy. “It’s good for the television stations, it’s good for the pharmaceutical companies, but it’s not good for public health.”

The US and New Zealand are the only two nations globally that allow drug companies to promote their products directly to the consumer – known as direct-to-consumer advertising (DTCA).

Kennedy said that because of pharmaceutical advertising in the US, Americans use more prescription drugs than anywhere else in the world, and yet, they have the worst outcomes.

Americans have the lowest life expectancy compared to other wealthy nations and the highest rate of avoidable deaths, despite spending nearly 18% of GDP on healthcare in 2021.

Kennedy told me he blames “the influence of the pharmaceutical lobby in Washington, and indirectly, the influence of media companies that earn some $18 billion in revenue annually from direct-to-consumer drug advertising.”

Drug advertising in the US

In the 80s, there were few prescription drug ads broadcast on US TV because the regulatory standard made it difficult to provide adequate information about drug labelling to consumers. David Kessler, FDA Commissioner between 1990 and 1997, also vigorously opposed DTCA.

But when Kessler left the agency, the new administration eased regulatory restrictions and the floodgates opened. Within a decade, DTCA went from US$2.1 billion in 1997 to US$9.6 billion in 2016.

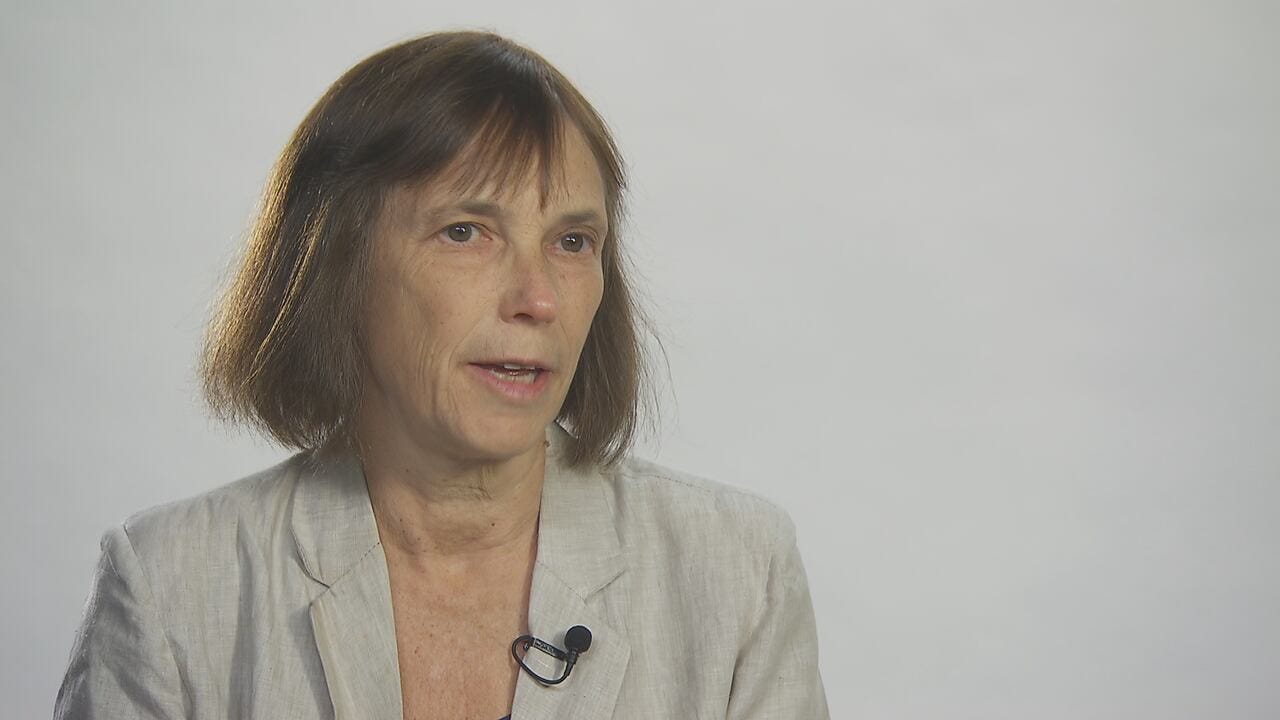

“They do it because it works,” said Barbara Mintzes, professor of evidence-based pharmaceutical policy at the University of Sydney. “Drug companies would not be spending the money if it did not lead to expanded sales.”

Proponents argue that DTCA empowers the consumer with information about diseases and drug treatments by encouraging informed discussions between patients and their medical providers. But Mintzes is not convinced.

“I totally agree that people need information on medicines but getting that information from advertising is not the same as getting it from an unbiased source,” said Mintzes.

Mintzes has long argued against DTCA saying, “There is no public health rationale and no reliable evidence that it leads to better care, public or patient empowerment, or to the type of information needed for shared informed treatment choices.”

Many Americans are unaware of the persuasiveness of DTCA. A national FDA survey found that 29% of consumers believed that only completely safe medicines could be advertised on TV. In California, it was 42% of consumers.

Advertised drugs offer little benefit

The decision about which drugs are advertised is not made on public health grounds, but on what will maximise profits.

“It's a marketing decision,” says Mintzes. “Often, it’s a small, select group of drugs that are very expensive, on patent, and are not necessarily the best available treatments in terms of effectiveness or safety.”

According to a recent study published in JAMA, most of Big Pharma’s spending (68%) on the top-selling prescription drugs in 2020, were of ‘low added benefit’ for patients.

The study’s lead author Michael DiStefano, a researcher at Johns Hopkins said it’s probably a strategy of the pharmaceutical industry to “drive patient demand for drugs that clinicians would be less likely to prescribe.”

“When a consumer sees these advertisements on TV or social media, they should really question if it’s the best drug for them and have a conversation with their provider,” said DiStefano.

Poor FDA oversight of DCTA

The FDA regulates the promotion of medicines and the content of DTCA, under the authority of the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA). It requires that advertising is accurate, and only promotes the drug for approved conditions, clearly stating harms and ways to get more information.

However, the agency lacks the resources to police it properly.

A 2002 Government Accountability Office report found the FDA’s oversight of DTCA was lacking. The agency had allowed some drug companies to repeatedly disseminate new misleading advertisements for the same drug.

Further, a change in the FDA’s procedures for reviewing draft regulatory letters led to a significant lag in issuing letters to demand the removal of misleading advertising - some regulatory letters were not even issued until after the advertising campaign had run its course.

Vioxx ads led to unnecessary deaths

From 1999 to 2004, Vioxx was among the most aggressively advertised medicines in the US. Merck spent more than US$100 million per year in advertising to consumers and generated annual sales of more than US$1 billion.

But Merck ran a deceptive advertising campaign, which misrepresented the safety of Vioxx and improperly concealed the drug’s increased risk of stroke. Vioxx was estimated to have caused 88,000–140,000 heart attacks in the USA alone - 44% of which were fatal.

A significant proportion of those people who died, took Vioxx after seeing it advertised on TV.

FDA promoted covid products

During the pandemic, the FDA began promoting covid-19 products - antivirals and vaccines – something that is not in the agency’s remit.

FDA commissioner Robert Califf, for example, repeatedly advertised the benefits of Pfizer’s antiviral drug paxlovid and covid-19 vaccines for reducing the risk of long covid.

“The FDA commissioner can't tweet like this,” wrote Vinay Prasad, a practicing haematologist-oncologist at the University of California San Francisco. “How does the FDA preserve the authority to regulate truthful marketing, when the FDA commissioner is a billboard for Pfizer? These claims are not validated by the highest methods. This is unbelievable.”

In addition, director of the FDA’s vaccine division Peter Marks, featured in multiple videos on the FDA’s website, encouraging people to take the newly authorised bivalent boosters.

“It always feels odd to see the FDA promote products,” said Jessica Adams, a regulatory affairs expert. “The agency used to go out of its way to respect patient-provider decision-making and not interfere with the practice of medicine.”

In fact, the FDA’s own homepage was promoting the covid-19 vaccines.

“The FDA acts like a cheerleading or marketing arm of pharma companies, not a regulatory agency” said Aaron Siri, attorney at Siri & Glimstad law firm. “By promoting these shots, the FDA has hopelessly conflicted itself from later admitting these products have serious issues.”

“It is not the role of the FDA to promote vaccines or advise people to get them. Its role is to objectively assess whether they are safe and effective to its standard,” added Siri.

FDA’s revolving door

Kennedy has renewed calls to put an end to the FDA→Big Pharma “revolving door” which leads to undue influence over the agency.

Ten of the last 11 commissioners have gone on to secure roles with the pharmaceutical or biotech industries they once regulated - most within a year or two of leaving the FDA (see table).

Califf was announced as FDA commissioner on 17 Feb 2022 (his second time). SEC filings indicate that he resigned from the board of directors of Centessa Pharmaceuticals, the day before the announcement.

“That is an indication of just how completely industry has captured this agency,” said Kennedy vowing to shake up the system if he becomes president.

“We will institute new rules extending the waiting period before former officials can enter industry, consulting, and lobbying. We want real public servants in positions of public trust,” he added.

Kennedy believes the key to reforming the FDA will be to put qualified people in positions from outside the pharmaceutical industry, and to call on whistle-blowers, dissidents, and other people of integrity from within the FDA.

The FDA did not comment on the agency’s ‘revolving door’, nor did it answer whether the agency had considered instituting an extended waiting period between the time officials leave the FDA and enter industry.

Abolish the FDA. After 100 years of politicians promising to do better, this is what we have.

It's not going to get better.

Insurance companies can evaluate drugs. They already crash-test cars.

I do love listening to the laundry list of side-effects of these drugs!