Since genomics expert Kevin McKernan discovered excess levels of plasmid DNA in Pfizer's COVID-19 mRNA vaccine, a significant concern has emerged regarding the potential for the fragments to increase cancer risk among recipients.

The primary worry is that these plasmid DNA fragments could randomly insert into the human genome, causing gene mutations through a process known as insertional mutagenesis.

Despite assurances from drug regulators and public health agencies that "COVID-19 vaccines do not change or interact with your DNA in any way," they have failed to provide any concrete analysis or data supporting their claims.

DNA integration has been demonstrated numerous times under controlled laboratory conditions.

For instance, a study in Nature’s Scientific Reports showed that when linear DNA fragments are introduced to cells, approximately 7% of transfected cells undergo DNA integration within hours.

In February, McKernan and his colleagues demonstrated that DNA fragments within Pfizer's vaccine could integrate into the genome of cultured ovarian cancer cell lines.

Critics have argued that these experiments in “cancer cells lines” do not represent what happens in normal tissue.

Now, Philip Buckhaults, a cancer genomics expert at the University of South Carolina, has provided new evidence that defies these criticisms.

His experiments have shown that plasmid DNA from mRNA vaccines can indeed integrate into the genome of normal human cells.

He shared his data on X.

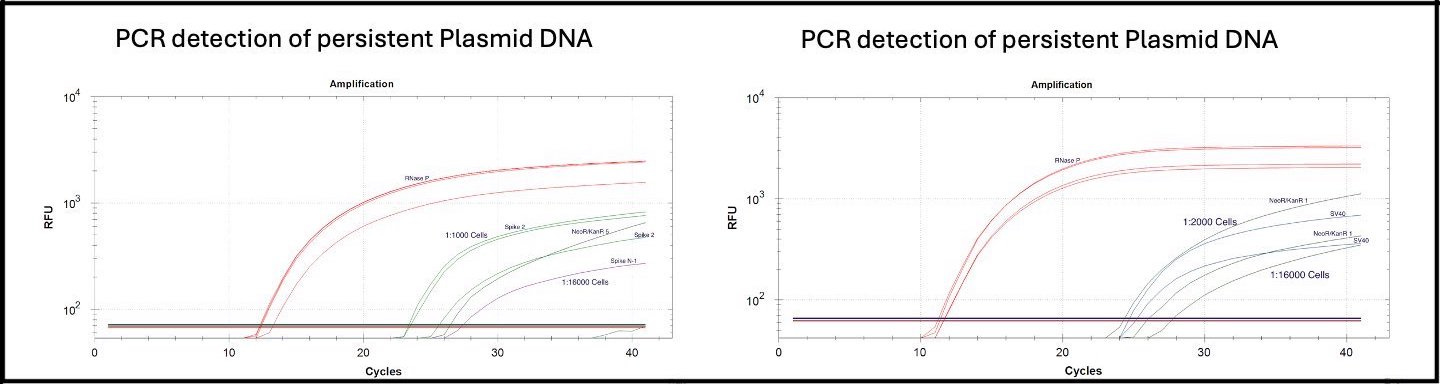

By growing human epithelial stem cells (organoids) from colon tissue, and “vaccinating” (mixing) them with mRNA vaccines, Buckhaults detected persistent plasmid DNA within the genomic DNA of these cells after a month, using qPCR.

These graphs indicate that a minority of the cells were transfected – between 1 in 1000 and 1 in 16,000 cells show they contain plasmid DNA one month later – and the “fragments” were from the spike gene, SV40 promoter and NeoKanR gene.

Buckhaults conducted this research partly in response to criticism from those who doubted his previous assertions, aiming to provide definitive evidence.

He shared on X, "This experiment was done mainly for the people who were paid to publicly ridicule this idea (and slander my reputation)."

The experiment cost “several thousands of dollars” wrote Buckhaults, “whereas the reputation slander cost the saboteurs nothing” referring to the personal and professional toll of public criticism, calling it "asymmetric reputation warfare."

Buckhaults suggested that his experimental method could be adopted by drug regulators, such as the US FDA, saying, “This would be a smart thing for the US FDA to start doing in house."

He also proposed that this method could serve as a new tool for assessing the "mutagenic potential" of the substances we ingest, potentially allowing us to predict DNA mutagens decades in advance.