Should you take a flu shot?

It’s that time of year when media campaigns urge Australians to get the flu jab—but what does the evidence reveal?

It’s autumn and Australian health authorities are ramping up their annual push for widespread flu vaccination.

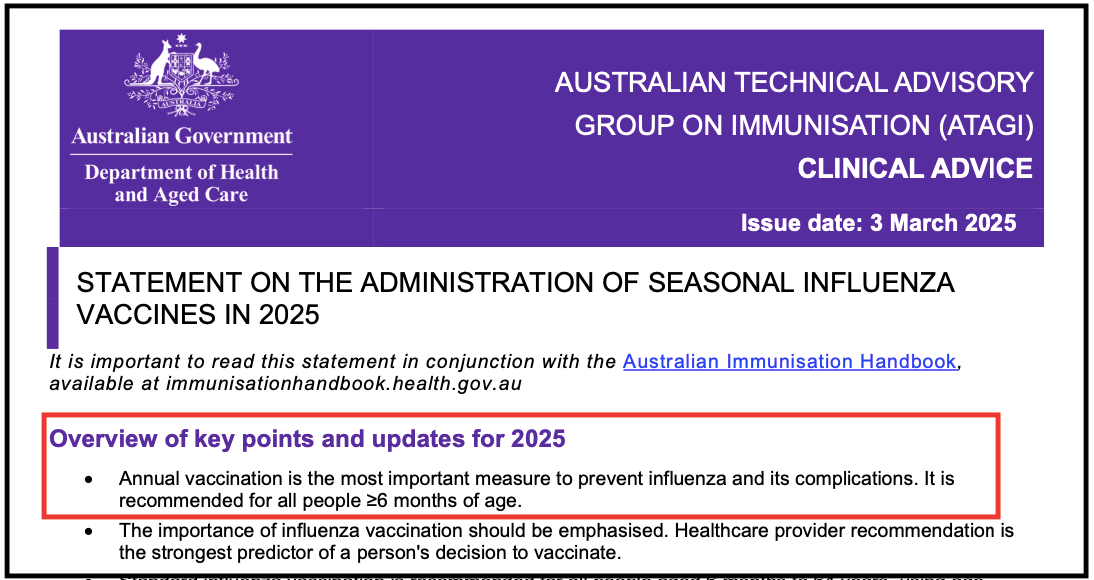

This year, they’re urging everyone aged six months and older to receive the jab ahead of the 2025 influenza season.

States like Victoria and New South Wales make it compulsory for healthcare workers to take the flu shot, part of a broader strategy to reduce transmission.

Authorities claim the vaccine is essential to prevent severe illness, reduce hospital admissions, and protect society’s most vulnerable. But do the data support these claims?

More than a decade ago, Peter Doshi, Associate Professor at the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy and Senior Editor at the BMJ, questioned the assumptions underpinning flu vaccine campaigns.

In a 2013 JAMA Internal Medicine editorial, he argued that flu vaccines do not reliably reduce outcomes that matter to patients—such as hospitalisation or death.

Twelve years on, little has changed. If anything, recent evidence has reinforced doubts about the vaccine’s effectiveness—and its necessity.

What do authorities say?

Public health agencies like the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)—widely criticised for conflicts of interest and politicisation—promote flu vaccines with efficacy rates ranging between 40% and 60%.

But even the CDC concedes that these estimates are drawn from observational studies that are prone to bias, particularly the “healthy user effect,” where healthier individuals are more likely to get vaccinated, skewing results.

A Cochrane review supports this concern. It found that in healthy adults aged 18 to 49, the vaccine probably reduced influenza from 2.3% to 0.9%. In practical terms, 71 people need to be vaccinated to prevent a single case—hardly compelling justification for mass vaccination.

The evidence is even weaker in older adults, who make up the majority of flu-related deaths.

Only one randomised trial has ever been conducted in community-dwelling older adults, and it was too small to determine whether the vaccine prevented hospitalisation or death.

According to the Cochrane review, evidence from randomised trials does not demonstrate a reduction in hospital admissions, bacterial pneumonia, or any other clinically meaningful outcomes.

Despite this, Australia’s official recommendation remains unchanged: an annual flu shot for everyone over six months of age.

Does the flu vaccine protect others?

A key argument for mandating flu vaccines for healthcare workers is that it helps protect vulnerable patients. However, this rationale is both ethically and scientifically questionable.

From an ethical perspective, compelling individuals to accept personal risk—however small—for the benefit of others raises serious questions about consent and bodily autonomy.

Scientifically, the evidence is also weak. A recent Cochrane review found that offering vaccination to healthcare workers made “little or no difference to the number of residents who get flu or go to hospital with a chest infection.”

Nevertheless, Victoria and New South Wales maintain mandatory flu vaccination policies for healthcare workers.

Elsewhere in Australia, such mandates are absent, though healthcare workers are still pressured to get vaccinated to shield vulnerable patients.

By contrast, the UK opts for a voluntary approach, not requiring flu jabs for its healthcare staff.

How deadly is influenza?

Much of the push for widespread flu vaccination hinges on the fear of death. But flu-related mortality figures are far less clear-cut than often portrayed.

In Australia, (pre-COVID) the estimated 300 to 1,000 yearly flu deaths come from statistical models, and often mix in other respiratory illnesses, like pneumonia, which aren’t always proven to be caused by influenza itself.

If flu vaccines were highly effective, a reduction in winter mortality would be expected as vaccination rates increased. Yet no such decline has been observed.

In fact, vaccine coverage among Australians aged 65 and over rose from 25% in 2000 to 75% in 2019, but flu-related deaths also increased—from 300–500 annually in the early 2000s to 953 deaths in 2019.

These trends cast serious doubt on the vaccine’s real-world impact.

A flawed strategy—is it better than nothing?

Some defenders of the flu vaccine argue that even if they “aren’t always perfect,” it's still “better than nothing.”

Government campaigns reinforce this view.

But Doshi warns this thinking fails to account for the vaccine’s potential to cause harm.

Cochrane reviews have highlighted significant gaps in the reporting of safety outcomes in flu vaccine trials, limiting our understanding of the vaccine’s true risk profile.

For example, Guillain-Barré Syndrome—a serious neurological disorder in which the immune system attacks the nerves—has long been associated with influenza vaccines, especially following the 1976 “swine flu” scare.

In another case, an uptick in narcolepsy cases in Finland and Sweden followed the rollout of the 2009 H1N1 vaccine, Pandemrix.

Closer to home, Australia suspended its 2010 seasonal flu vaccine programme for children under five after an alarming number of cases of febrile convulsions—about 1 in every 110 children—were reported following immunisation.

Of further concern, research reported that annual influenza vaccination hampers the development of CD8 T-cell immunity in children—a key component of long-term protection.

Put simply, “better than nothing” ignores the fact that vaccines can cause harm—and when those harms are under-reported in clinical trials and post-market surveillance, it becomes difficult to accurately weigh harms against benefits.

New evidence from the Cleveland Clinic

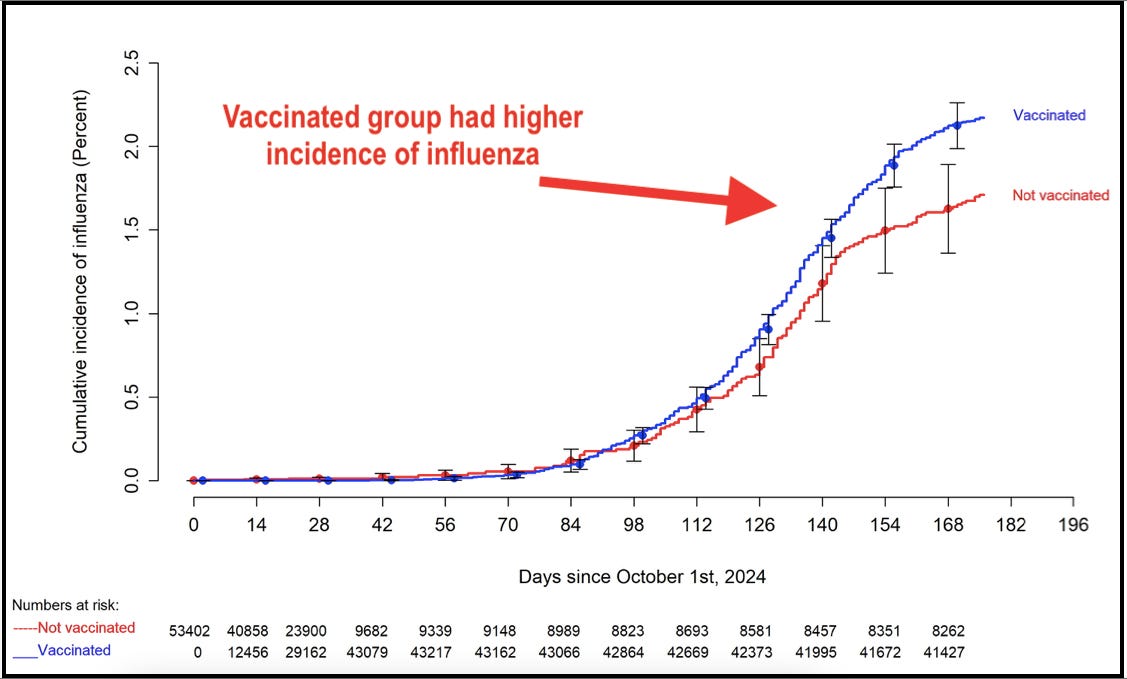

Adding to concerns, a recent preprint study from the Cleveland Clinic tracked more than 53,000 employees during the 2024–2025 flu season. Despite an 82% vaccination rate, the study found the vaccine had not been effective in preventing influenza.

In fact, flu cases were actually higher among the vaccinated than the unvaccinated. The vaccinated group faced a 27% increased risk of infection, with an overall vaccine effectiveness of –26.9% (negative effectiveness).

The researchers attributed this to a likely mismatch between the vaccine and circulating strains and cautioned that it may be unrealistic to expect high effectiveness every year.

This mirrors findings from Canada during the 2008–2009 flu season, where the seasonal flu shot was linked to a 1.4 to 2.5 times greater risk of contracting the H1N1 pandemic flu, possibly due to immune system interactions or strain-specific effects.

These findings align with Doshi’s long-standing concerns about the overstatement of benefits, underappreciation of risks, and the need for more robust evidence before endorsing universal flu shot policies.

Time for a rethink?

Since Doshi raised these concerns in 2013, influenza vaccination policies have remained largely unchanged.

Australia needs to reconsider its strategy.

Despite widespread promotion, the flu vaccine still shows no clear mortality benefit in the elderly, no reduction in hospitalisations, no proven impact on transmission, and only modest symptom reduction in healthy adults.

Doshi’s warning back then, remains just as relevant today—we need better trials, transparent data, and a realistic appraisal of flu’s actual burden.

Even Cochrane has acknowledged the stagnation in flu vaccine research. Recently, the authors made the unusual decision to “stabilise” its three long-running reviews on influenza vaccines, citing a lack of meaningful new evidence over time.

After decades of study, the core findings have not significantly changed—casting further doubt on whether the current policies are truly evidence-based.

Until that changes, Australians must weigh the evidence—not just the slogans—when deciding whether to roll up their sleeve this flu season.

Yes indeed about the Guillain-Barré Syndrome. My late dad hardly ever got sick. He was a mighty man that chopped down trees into his late 60s. One day, convinced by the local doctor, he gets the flu shot (he never got it before). Week later, gets the flu ! We laughed at the irony. Month later, his feet and hands go numb, he can't stand. Multiple tests and doctors guessing, mini stroke ? Infection? Finally a neurologist nails it ! The above named syndrome....and it got worse because it was the recurring type.

Has to have plasma infusions every month. Not that it did much good ! Whole situation reduced him from a vital healthy independent man who did the hard yakka to a infirm shell of a human. Hard to watch !

I brought up the flu shot theory with the original neurologist but he said "Not enough evidence". But it is enough evidence for me ! Flu Shot? NO THANKS ! 😤

Agree with the post and your comments Nic. Here in the USA, I was told our flu shots were based on what Australia’s strain was. Starts there and spreads west. I think it’s time to let our natural immune system work. Leave the poisons out. Closer to 80 than 70! Retired since November, 2013. Believed what they said until the COVID jab rolled out. We just said “no!” One of us always got sick each winter. I told my husband we are done. So glad we made a wise decision. Common sense.