For several years now, drug regulators have dismissed concerns about DNA contamination in Covid-19 mRNA vaccines.

In 2023, when genomics researcher Kevin McKernan first reported excessive levels of synthetic DNA fragments in Pfizer’s vaccine, authorities ignored the findings.

Then, as other laboratories began testing vaccine vials, the same pattern emerged. Different groups, using different methods, kept finding elevated DNA levels — while regulators insisted the excess contamination wasn’t there.

Each time, officials pointed to their own testing, which they said showed any residual DNA left over from manufacturing was within permissible limits.

So why the stark difference in results?

It turns out the independent laboratories were not wrong — it was the regulators who were relying on a testing method that was never designed to detect the problem.

The test that made the problem disappear

mRNA vaccines are manufactured using a circular DNA template known as a plasmid.

Once the mRNA is transcribed, manufacturers add an enzyme called DNase I, intended to break down any remaining DNA. Regulators then test the final product to confirm that this cleanup step has worked.

That testing relies on a laboratory technique called quantitative PCR, or qPCR.

But qPCR does not measure total DNA. It only detects a specific DNA sequence chosen in advance. If that sequence is present at very low levels, regulators infer that little DNA remains overall.

In this case, the sequence regulators chose to monitor was the kanamycin resistance, or KAN, gene — a small fragment of the DNA plasmid.

The assumption was that if the KAN signal was low, the rest of the plasmid must also have been destroyed.

That assumption is wrong.

The DNase blind spot

McKernan and colleagues have recently published a preprint explaining why the test used by regulators is not fit for purpose.

During mRNA manufacturing, some of the newly produced RNA remains tightly bound to its original DNA template, forming structures known as RNA–DNA hybrids.

These hybrids are highly resistant to digestion by DNase I. Other parts of the plasmid that are not bound to RNA — including the KAN gene — are efficiently degraded and disappear readily.

That’s why, when regulators test specifically for KAN, they consistently detect very little residual DNA — and conclude that the cleanup step was successful.

What that test fails to reveal is the DNA that remains bound within these RNA–DNA hybrid structures — DNA that persists in the final product.

This is what McKernan describes as “hiding the ball”

Regulatory choices

This was not the result of scientific ignorance or inadequate laboratory capability.

Regulatory submissions to the European Medicines Agency (EMA) show that manufacturers had already developed and validated qPCR assays capable of detecting spike-related DNA.

So, those tools existed — they just weren’t used.

Instead, regulators and manufacturers continued to rely on measuring the KAN gene — the fragment least likely to survive DNase treatment.

Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) adopted this very approach.

Freedom-of-information documents show the TGA relied on qPCR detection of the KAN gene and concluded that residual DNA in multiple Pfizer and Moderna vials was all within regulatory limits.

The TGA then gaslit the public, dismissing any opposing evidence as “misinformation,” while knowing its testing method was incapable of detecting the problem.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) followed a similar path.

In January 2025, students working in the FDA’s own laboratory detected DNA contamination in Pfizer’s product ranging from six to 470 times above regulatory limits.

The work was conducted using FDA equipment and reagents, under the supervision of senior FDA scientists.

When confronted with the evidence, the FDA remained silent. There was no recall, and no safety alert. Instead, the agency distanced itself from the work.

This was not a failure to see the problem. It was a shared regulatory decision — across agencies — to rely on a test that made the problem disappear.

They knew all along

None of this was unforeseeable.

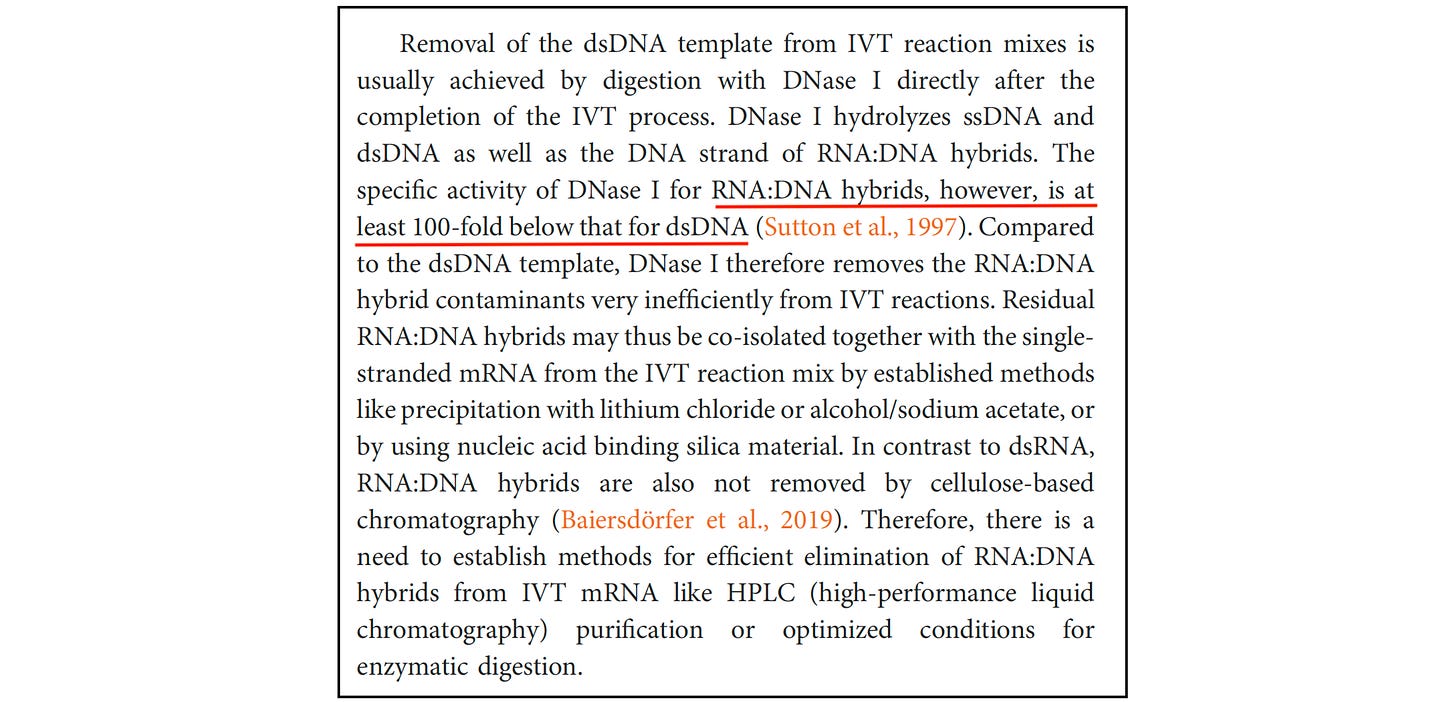

Several scientific papers have documented that DNase treatment can leave RNA–DNA hybrids largely intact while degrading other plasmid regions.

Even BioNTech — the company that partnered with Pfizer — has acknowledged the limitation. In a technical review, the company noted that DNase I is at least 100 times less effective at degrading RNA-DNA hybrids than ordinary double-stranded DNA.

Despite this, regulators did not revise their approach, continuing to rely on a test that systematically underestimates residual DNA.

Why this won’t go away

For a time, regulators portrayed residual DNA as a theoretical concern — speculative and biologically implausible.

But that position is no longer defensible.

Recent peer-reviewed research has described plausible pathways by which residual DNA entering human cells could contribute to unusually rapid cancer progression, or even the sudden return of cancers previously thought to be stable.

These include mechanisms by which foreign DNA can disrupt normal cellular controls, trigger chronic inflammatory signalling, or interfere with systems that normally suppress tumour growth.

What remains missing is something far more basic: any clinical evidence establishing a safe level of residual DNA in these vaccines.

Regulators exist to protect the public — not to obscure risk or shield manufacturers from scrutiny.

The scandal here is not that regulators lacked the science. It’s that they knew their testing was flawed — and used it anyway.

That isn’t regulatory failure…. that is malfeasance.